Buchwald et al published one of the many interesting papers in a recent special issue on motor speech disorders in the Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research. In their paper they outline a common approach to speech production, one that is illustrated and discussed in some detail in Chapters 3 and 7 of our book, Developmental Phonological Disorders: Foundations of Clinical Practice. Buchwald et al. apply it in the context of Acquired Apraxia of Speech however. They distinguish between patients who produce speech errors subsequent to left hemisphere cardiovascular accident as a consequence of motor planning difficulties versus phonological planning difficulties. Specifically, in their study there are four such patients, two in each subgroup. Acoustic analysis was used to determine whether their cluster errors arose during phonological planning or in the next stage of speech production – during motor planning. The analysis involves comparing the durations of segments in triads of words like this: /skæmp/ → [skæmp], /skæmp/ → [skæm], /skæm/ → [skæm]. The basic idea is that if segments such as [k] in /sk/ → [k] or [m] in /mp/ → [m] are produced as they would be in a singleton context, then the errors arise during phonological planning; alternatively, if they are produced as they would be in the cluster context, then the deletion errors arise during motor planning. This leads the authors to hypothesize that patients with these different error types would respond differently to intervention. So they treated all four patients with the same treatment, described as “repetition based speech motor learning practice”. Consistent with their hypothesis, the two patients with motor planning errors responded to this treatment and the two with phonological planning errors did not as shown in the table of pre- versus post-treatment results.

However, as the authors point out, a significant limitation of this study is that the design is not experimental. Having failed to establish experimental control either within or across speakers it is difficult to draw conclusions.

I find the paper to be of interest on two accounts nonetheless. Firstly, their hypothesis is exactly the same hypothesis that Tanya Matthews and I posed for children who present with phonological versus motor planning deficits. Secondly, their hypothesis is fully compatible with the application of a single subject randomization design. Therefore it provides me with an opportunity to follow through with my promise from the previous blog, to demonstrate how to set up this design for clinical research.

For her dissertation research, Tanya identified 11 children with severe speech disorders and inconsistent speech sound errors who completed our full experimental paradigm. These children were diagnosed with either a phonological planning disorder or a motor planning disorder using the Syllable Repetition Task and other assessments as described in our recently CJSLPA paper, available open access here. Using those procedures, we found that 6 had a motor planning deficit and 5 had a phonological planning deficit.

Then we hypothesized that the children with motor planning disorders would respond to a treatment that targeted speech motor control: much like Brumbach et al., it included repetition practice according to the principles of motor practice during the practice parts of the session but during prepractice, children were taught to identify the target words and to identify mispronunciations of the target words so that they would be better able to integrate feedback and self-correct during repetition practice. Notice that direct and delayed imitation are important procedures in this approach. We called this the auditory-motor integration (AMI approach).

For children with Phonological Planning disorders we hypothesized that they would respond to a treatment similar to the principles suggested by Dodd et al (i.e., see core vocabulary approach). Specifically the children are taught to segment the target words into phonemes, associating the phonemes with visual cues. Then we taught the children to chain the phonemes back together into a single word. Finally, during the practice component of each session, we encouraged the children to produce the words using the visual cues when necessary. An important component of this approach is that auditory-visual models are not provided prior to the child’s production attempt-the child is forced to construct the phonological plan independently. We called this the phonological memory & planning (PMP) approach.

We also had a control condition that consisted solely of repetition practice (CON condition).

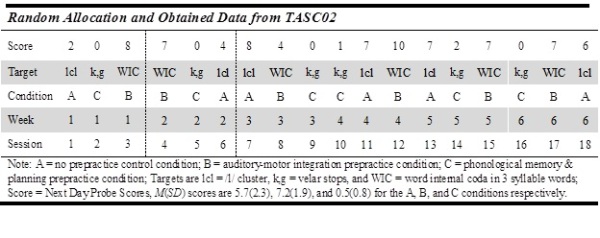

The big difference between our work and Brumbach et al. is that we tested our hypothesis using a single subject block randomization design, as described in our recent tutorial in Journal of Communication Disorders. The design was set up so that each of the 11 children experienced all three treatments. We chose 3 treatment targets for each child, randomly assigned the targets to each of the three treatments, and then randomly assigned the treatments to each of three sessions, scheduled to occur on different days of the week, 3 sessions per week for 6 weeks. You can see from the table below that each week counts as one block, so there are 6 blocks of 3 sessions for 18 sessions in total. The randomization scheme was generated blindly and independently using computer software for each child. The diagram below shows the treatment schedule for one of the children with a motor planning disorder.

This design allowed us to compare response to the three treatments within each child using a randomization test. For this child, the randomization test revealed a highly significant difference in favour of the AMI treatment as compared to the PMP treatment, as hypothesized for children with motor planning deficits. I don’t want to scoop Tanya’s thesis because she will finish it soon, before the end of 2017 I’m sure, but the long and the short of it is that we have a very clear results in favour of our hypothesis using this fully experimental design and the statistics that are licensed by it. I hope you will check out our tutorial on the application of this design: we show how flexible and versatile this design can be for addressing many different questions about speech-language practice. There is much exciting work being done in the area of speech motor control and this is a design that gives researchers and clinicians an opportunity to obtain interpretable results with small samples of children with rare or idiosyncratic profiles.

Reading

Buchwald, A., & Miozzo, M. (2012). Phonological and Motor Errors in Individuals With Acquired Sound Production Impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 55(5), S1573-S1586. doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2012/11-0200)

Rvachew, S., & Matthews, T. (2017). Using the Syllable Repetition Task to Reveal Underlying Speech Processes in Childhood Apraxia of Speech: A Tutorial. Canadian Journal of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology, 41(1), 106-126.

Rvachew, S., & Matthews, T. (2017). Demonstrating treatment efficacy using the single subject randomization design: A tutorial and demonstration. Journal of Communication Disorders, 67, 1-13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2017.04.003