It is probable that you have seen at least references to the Sperry, Sperry & Miller (2018) paper in Child Development because it made a big splash in the media–the claim of “challenging” Hart & Risley’s (1992/1995) finding of a “30 million word gap” in language input to children with “poor” versus “professional” parents caused a lot of excitement. You may not have seen the follow-up commentary by Golinkoff, Hoff et al and then then the reply by Sperry et al. I want to say something about vocabulary and phonological processing with these papers as a jumping off point which means I have to summarize their debate as efficiently as I can–no easy task because there is a lot going on in those papers but here is the short version:

- Sperry, Sperry & Miller (paradoxically) present a very good review of the literature showing that cross-culturally, language input provided directly TO children (i.e., the words that the child hears) predicts language outcomes. This is true even though there is a lot of variation in how much language is directed to children (versus spoken in the vicinity of children) across different cultures and SES strata: regardless of those differences, it is the child-directed speech that matters to rate of language development. Nonetheless, they make the point that overheard speech is understudied and present data indicating that children in poor families across a variety of different ethnic communities might hear and overhear as much speech as middle-class children. Their study is not at all like the Hart & Risley study and therefore the media claims of a “failure to replicate” are inappropriate and highly misleading.

- Golinkoff, Hoff et al reiterate the argument that they have been making for decades: children do well in school when they have good language skills; language skills are driven by the quantity and quality of child-directed inputs provided. The focus on the 30 million word gap has led to the development of effective parenting practices and interventions and a de-emphasis on Hart & Risley’s findings would be harmful to children in lower SES families (note that no one is arguing that all poor children receive inadequate inputs or that all racialized children are poor either, these are straw-man arguments).

- Sperry et al reply to this comment by saying “Based on the considerable research already cited here and in our study, we assert that it is a mistake to claim that any group has poor language skills simply because their skills are different. Furthermore, we believe that as long as the focus remains on isolated language skills (such as vocabulary) defined by mainstream norms, testing practices, and curricula, nonmainstream children will continue to fail. We believe that low-income, working class, and minority children would be more successful in school if pedagogical practices were more strongly rooted in a strengths-based approach…”

We can all get behind a call for culturally sensitive and fair tests I am sure. As speech-language pathologists we are very motivated to take a strengths-based approach to assessment as well. It is also important to understand that when mothers are talking with their children, they are not transmitting words alone, but also culture. Richman et al. (1992) describe how middle-class mothers in Boston engaged their infants in “emotionally arousing conversational interactions” whereas Gusii mothers “see themselves as protecting their infants” and focused on soothing interactions that moderated emotional excitement; in this same paper, increased maternal schooling was observed to be associated with increased verbal responsiveness to infants by Mexican mothers when compared to mothers from the same community with less education. Therefore, encouraging a “western” style of mother-infant vocal interaction may well conflict with the maternal role of enculturating her infant to valid social norms that differ from western or mainstream values. The call to respect those cultural norms, reflected in Sperry et al’s reply obviously deserves more serious consideration than shown in Golinkoff et al’s urgent plea to maximize vocabulary size.

Nonetheless, Sperry et al are engaging in some wishful thinking when they claim that “young children in societies where they are seldom spoken to nonetheless attain linguistic milestones at comparable rates.” In fact, the only evidence they point to in support of this claim pertains to pointing as a form of nonverbal communication. While it is evidently true that culture is a strong determinant of mother-infant interactional style, it makes no sense to argue that differences in the style of interaction and the amount of linguistic input make no difference to language learning. Teaching interactions vary with culture but learning mechanisms do not (unless you are arguing that there are substantial genetic variations in neurolinguistic mechanisms across ethnic groups and I am absolutely not arguing that, the complete opposite). When Linda Polka and I were studying selective attention in infant speech perception development we talked about speech intake as opposed to speech input. Certainly there may be different ways to engage the infant’s attention but ultimately the amount and quality of linguistic input that the child actively receives will impact the time course of language development. Immigrant parents may not be aiming for western middle class outcomes for their children but when they are, tools to increase vocabulary size in the majority language will be essential.

The other part of Sperry et al’s argument is that children who are not middle class speakers of English in North America might have strengths in other aspects of language (story telling, for example) that must be valued. Vocabulary is deemed to be an isolated skill. This is the part of their argument that I find to be most problematic. Vocabulary is central to all aspects of language learning: phonology and phonological processing, morphology, and syntax, in the oral and written domains. Words are the heart and soul of language and language learning. It is difficult to understand how the child could achieve excellence as a story teller without a good vocabulary. Furthermore, vocabulary is not learned in isolation from all those other aspects of language including the social, pragmatic and cultural. For those children receiving speech-language pathology services, a large vocabulary is protective: if the child for whatever reason has phonological or language processing deficits that make it difficult to learn phonological awareness or decoding skills or morphology or syntax, a large vocabulary can help compensate for those weaknesses. For a speech-language pathologist, a strengths-based perspective may well mean engaging all the people in the child’s environment to build on the child’s vocabularies in the home and school languages as a means of compensating for difficulties in these other areas of language. More typically, what I see is a narrow focus on phonological awareness or morphology or syntax because these skills are weaker and presumably more “important.” But vocabulary is one area where nonprofessionals, paraprofessionals and other professionals can make a huge difference and what a difference it makes!

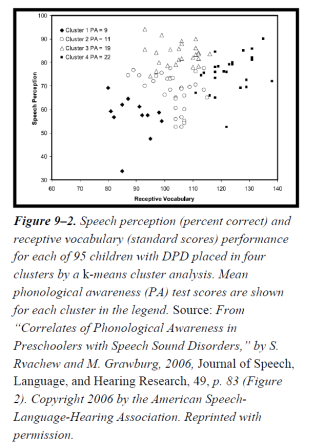

Further to this topic I am adding below an excerpt from our book Rvachew & Brosseau-Lapré (2018) along with the associated Figure. I also recommend papers by Noble and colleagues on the neurocognitive correlates of reading (an effect that I am sure is also mediated by vocabulary size).

“Vocabulary skills may be an area of relative strength for children with DPD and therefore it may seem unnecessary to teach their parents to use dialogic reading techniques to facilitate their child’s vocabulary acquisition. If the child’s speech is completely unintelligible, low average vocabulary skills are not likely to be the SLP’s highest priority and with good reason! However, good vocabulary skills may be a protective factor for children with DPD with respect to literacy outcomes. Rvachew and Grawburg (2006) conducted a cluster analysis based on the speech perception, receptive vocabulary, and phonological awareness test scores of children with DPD. The results are shown graphically in Figure 9–2. In this figure, receptive vocabulary (PPVT–III) standard scores are plotted against speech perception scores (SAILS; /k/, /s/, /l/, and /ɹ/ modules), with different markers for individual children in each cluster. The figure legend shows the mean phonological awareness (PA) test score for each cluster. The normal limits for PPVT performance are between 85 and 115. The lower limit of normal performance on the SAILS test is a score of approximately 70% correct. Clusters 3 and 4 achieved a mean PA test score within normal limits (i.e., a score higher than 15), whereas Clusters 1 and 2 scored below normal limits on average. The figure illustrates that the children who achieved the highest PA test scores had either exceptionally high vocabulary test scores or very good speech perception scores. The cluster with the lowest PPVT–III scores demonstrated the poorest speech perception and phonological awareness performance. These children can be predicted to have future literacy deficits on the basis of poor language skills alone (Peterson, Pennington, Shriberg, & Boada, 2009). The contrast between Clusters 2 and 3 shows that good speech perception performance is the best predictor of PA for children whose vocabulary scores are within the average range. All children with exceptionally high vocabulary skills achieved good PA scores, however, even those who scored below normal limits on the speech perception test. The mechanism for this outcome is revealed by studies that show an association between vocabulary size and language processing efficiency in 2-year-old children that in turn predicts language outcom es in multiple domains over the subsequent 6 years (Marchman & Fernald, 2008). Individual differences in processing efficiency may reflect in part endogenous variations in the functioning of underlying neural mechanisms; however, research with bilingual children shows that the primary influence is the amount of environmental language input. Greater exposure to language input in a given language “deepens language specific, as well as language-general, features of existing representations [leading to a] synergistic interaction between processing skills and vocabulary learning” (Marchman & Fernald, 2008, p. 835). More specifically, a larger vocabulary size provides access to sublexical segmental phonological structure, permitting faster word recognition, word learning, and metalinguistic understanding (Law and Edwards, 2015). From a public health perspective, teaching all parents to maximize their children’s language development is part of the role of the SLP. For children with DPD it is especially important that parents not be so focused on “speech homework” that daily shared reading is set aside. SLPs can help the parents of children with DPD use shared reading as an opportunity to strengthen their child’s language and literacy skills and provide opportunities for speech practice (p. 469).”.

es in multiple domains over the subsequent 6 years (Marchman & Fernald, 2008). Individual differences in processing efficiency may reflect in part endogenous variations in the functioning of underlying neural mechanisms; however, research with bilingual children shows that the primary influence is the amount of environmental language input. Greater exposure to language input in a given language “deepens language specific, as well as language-general, features of existing representations [leading to a] synergistic interaction between processing skills and vocabulary learning” (Marchman & Fernald, 2008, p. 835). More specifically, a larger vocabulary size provides access to sublexical segmental phonological structure, permitting faster word recognition, word learning, and metalinguistic understanding (Law and Edwards, 2015). From a public health perspective, teaching all parents to maximize their children’s language development is part of the role of the SLP. For children with DPD it is especially important that parents not be so focused on “speech homework” that daily shared reading is set aside. SLPs can help the parents of children with DPD use shared reading as an opportunity to strengthen their child’s language and literacy skills and provide opportunities for speech practice (p. 469).”.